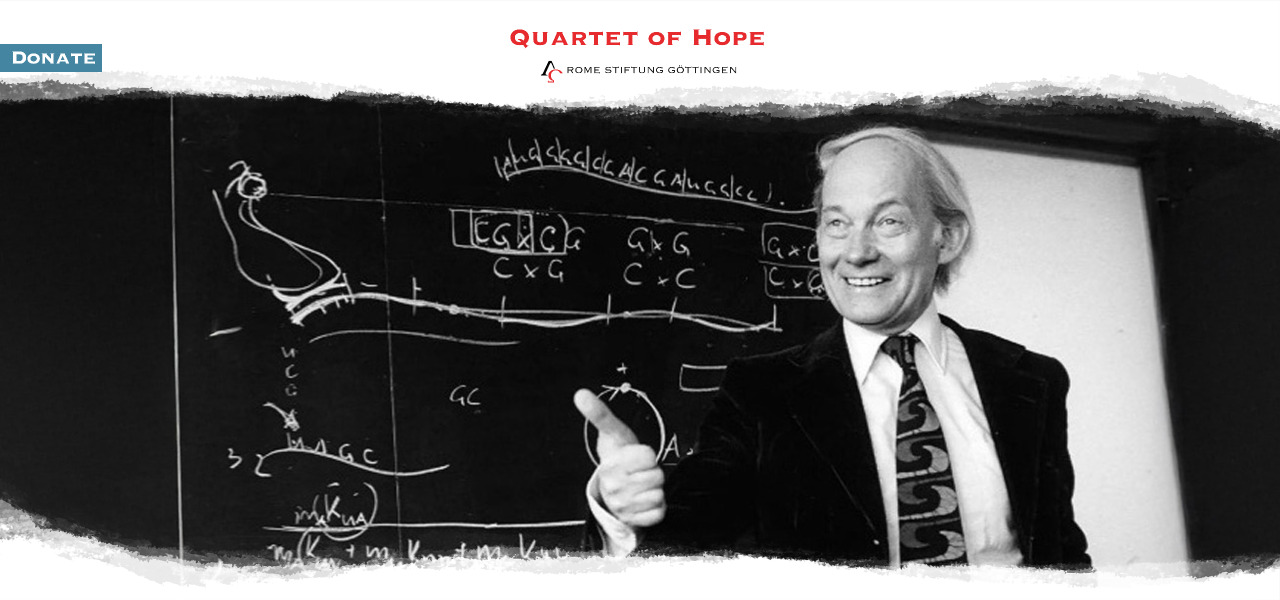

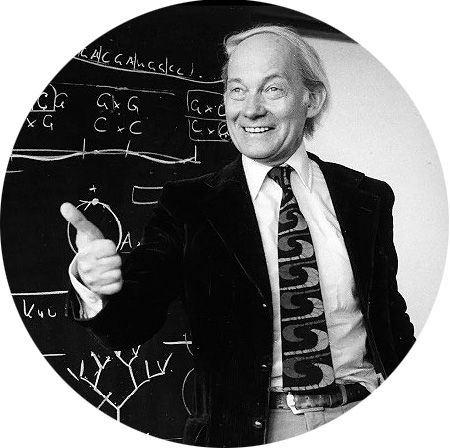

Manfred Eigen

1927 Bochum – 2019 Göttingen

Manfred Eigen was born into a family of musicians in Bochum. He studied physics and chemistry at the University of Göttingen from 1945, where he also obtained his doctorate under Arnold Eucken in 1951. In 1953, Karl Friedrich Bonhoeffer brought him to the Max Planck Institute for Physical Chemistry in Göttingen, where he became a scientific member in 1958, head of the Department of Chemical Kinetics in 1962 and director of the institute in 1964. He created the interdisciplinary department, which he was able to expand considerably in 1971 (biophysical chemistry since 1972). From 1965, he was an honorary professor at the TU Braunschweig.

Manfred Eigen developed kinetic methods for investigating extremely fast biochemical reactions, which he first recorded using the relaxation method. In 1967, together with Ronald George Wreyford Norrish and George Porter, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for research into extremely fast chemical reactions. This was followed in 1971 by the publication of a fundamental work on the self-organization of matter and the evolution of biological macromolecules, which he verified experimentally (the beginning of evolutionary biotechnology). Since then, Eigen’s name has been associated with the theory of the “hypercycle”, the cyclic linking of reaction cycles as an explanation for the self-organization of prebiotic systems, which he described together with Peter Schuster in 1979. The Eigen-Wilkins mechanism was named after him. Eigen founded two biotechnology companies, Evotec and Direvo, which are active in the fields of high-throughput screening and directed evolution.

From 1983 to 1993, Eigen was President of the German National Academic Foundation. In this role, he called for the formation of an elite of achievers. He was patron of the annual XLAB Science Festival in Göttingen.

The Manfred Eigen Foundation, which is a “dependent foundation within the private assets of the Max Planck Society”, is in existence since spring 2015. It supports scientific projects at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry.

Manfred Eigen’s vision was a scientific unity of the natural sciences. The fusion of physics, chemistry and biology into ultimately one body of knowledge is reflected in his idea of a uniform principle of development in the form of variation and selection in the Darwinian sense. Towards the end of his scientific career, he pursued the theory that selection underlies the entire development of the universe, as expressed in his last book, From Strange Simplicity to Familiar Complexity.

Manfred Eigen died in February 2019 at the age of 91.

Additional awards: 1962 Otto Hahn Prize, 1964 Member American Academy of Arts and Leopoldina, 1965 Member Academy of Sciences in Göttingen, 1971 Honorary Member of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, 1973 Member Order Pour le Mérite, 1976 Member Soviet Academy of Sciences, Austrian Decoration of Honor for Science and Art, 1977 Member Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 1980 Lower Saxony Prize for Science, 1989 Member of Academia Europaea, 1992 Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize, 1994 Helmholtz Medal, with Rudolf Rigler and Max Planck Research Prize, 2005 Lifetime Achievement Award Institute of Human Virology Baltimore, 2007 Golden Goethe Medal, 2011 Wilhelm Exner Medal, various honorary citizenships and honorary doctorates.

Music: Eigen played the piano since pre-school age. He appeared publically with piano concertos by JC Bach and J Haydn at the age of twelve. World War II interrupted his music studies, which he resumed after studying physics and chemistry. He had lessons with Rudolf Hindemith, brother of Paul. Manfred Eigen recorded Mozart piano concertos with the New Orchestra of Boston under David Epstein and the Basel Chamber Orchestra under Paul Sacher, with whom he had a close friendship since the 1960s. Both were striving to establish an institute for music research in Germany within the Max Planck Society, an interdisciplinary “Music Bauhaus”.

This project intended to bring the research of scientists and musicians close together. Leading representatives of various disciplines met for regular discussions in the “Hinterzarten Circle” to concretize the idea. Among those involved were many renowned scientists, including Werner Heisenberg, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker and Konrad Lorenz. Famous personalities such as the philosophers Georg Picht and Theodor Adorno were also involved. From the world of music, Paul Sacher was joined by violinist Yehudi Menuhin, composer and conductor Pierre Boulez and flautist Aurèle Nicolet. Despite the commitment of its prominent supporters, the project was not realized in Göttingen. With the same impetus, in France, the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique was opened at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1977 and still exists today. The first director of the institute was Pierre Boulez, who would have taken over the management of the German institute.

Max Perutz

1914 Wien – 2002 Cambridge

Max Ferdinand Perutz was born on 19 May 1914 into a wealthy Viennese textile industrialist family of Jewish origin. He studied at the University of Vienna from 1932. It was there that his interest in biochemistry was awakened, particularly through courses with Friedrich Wessely.

In 1936, he went to England and joined a crystallography research group at the Cavendish Laboratory of the University of Cambridge as a research assistant under John Desmond Bernal. Under the supervision of William Lawrence Bragg, he completed his Ph.D. In Cambridge, he also began researching haemoglobin, which is responsible for the transport of oxygen in the blood and was to occupy him for most of his research career.

After the so-called ‘Anschluss’ of Austria to Nazi Germany in 1938, Perutz was expelled from the country because of his Jewish origins. When the Second World War broke out, Perutz was deported from England to Canada along with other people of German or Austrian origin and interned in a mixed refugee/prisoner camp. Perutz worked there as a camp teacher for the refugees.

During the war, he worked on the Habbakuk project, a research project on the construction of an aircraft platform in the middle of the Atlantic on which planes were to be supplied and refuelled. For this purpose, he investigated the newly discovered substance Pykrete, a mixture of ice and wood fibres. He also carried out early-stage experiments with Pykrete under the Smithfield Meat Market in London. Perutz had been selected for this research project because he had conducted research into the changes in crystal arrangements in the layers of glacial ice before the war. After the war, he also briefly returned to glaciology, demonstrating, among other things, how glaciers flow. Perutz had obtained his doctorate in 1940, married in 1942 and had been the father of a daughter since 1944 – he continued his research as a glaciologist on the side.

In 1947, as a professor in Cambridge, he founded the Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB), which he headed until 1979. Francis Crick, Hugh Huxley, James Watson, Sydney Brenner, Fred Sanger and Aaron Klug all worked there. With Perutz as director, the institute became the birthplace of molecular biology, from which fifteen Nobel Prize winners emerged. In Cambridge, he also became a member of Peterhouse, where he was made an ‘Honorary Fellow’ in 1962. He took great care of the new members and was a regular and popular speaker at the Kelvin Club, the college’s scientific society.

In 1953, Perutz developed a new method for deciphering protein structures by labelling them with heavy atoms. Almost at the same time, LMB colleagues Francis Crick and James Watson had determined the structure of DNA. In 1959, Perutz then created the first three-dimensional haemoglobin model, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1962 together with his colleague John Kendrew, who had deciphered the structure of myoglobin. In the same year, Watson, Crick and Maurice Wilkins received the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

At the 600th anniversary celebrations of the University of Vienna, he opposed the awarding of honorary doctorates to former Nazi officials (they got their documents sent home instead of being invited).

Max F. Perutz continued to work at the LMB after his retirement. A later area of research were the differences in the haemoglobin structures of various species in order to adapt to different habitats and behavioural patterns. In the last years of his life, Perutz focussed on the changes in protein structures caused by Huntington’s and other neurodegenerative diseases. He showed that Huntington’s disease is linked to the number of glutamine repeats, as these combine to form what he called an ‘opposing zip’.

He began yet another career as an essayist, writing regular articles on scientific books and topics for the New York Review of Books. After the attack on 11 September, he appealed to Tony Blair and spoke out against military retaliation to protect innocent lives.

He was closely associated with music throughout his life. His favourite sonata was L. v. Beethoven’s Op.109 in E major. He died in Cambridge on 6 February 2002.

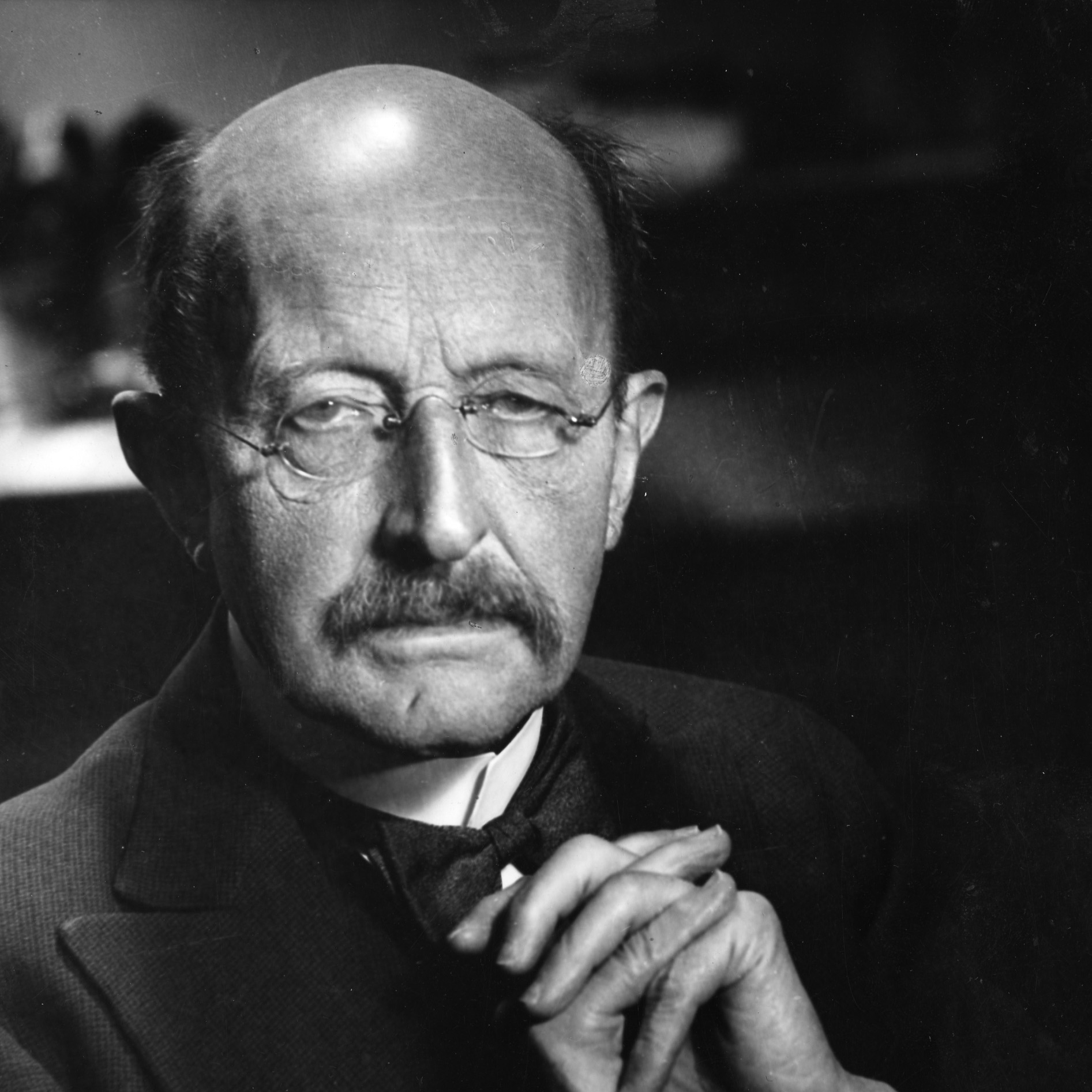

Max Planck

1858 Kiel – 1947 Göttingen

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck was born in Kiel in 1858. His father was a professor of constitutional law at the University of Kiel and later in Göttingen. Planck studied at the universities of Munich and Berlin, including under Kirchhoff and Helmholtz, and obtained his doctorate in Munich in 1879. In 1889, he became associate professor of theoretical physics in Kiel and succeeded Kirchhoff as professor at the University of Berlin. From 1926 to 1937, he was President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science.

Planck’s first work focussed on thermodynamics. At the same time, he worked on the problems of radiation processes and showed that these were to be regarded as electromagnetic. These studies led him to the problem of energy distribution in the spectrum of full radiation. The experimental observations of the wavelength distribution of the energy emitted by a black body as a function of temperature contradicted the predictions of classical physics.

Planck succeeded in deriving the relationship between the energy and the frequency of the radiation. His work on this relationship with the universal (Planck) constant, published in 1900, is Planck’s most important work and marked a turning point in the history of physics.

Planck’s work on quantum theory was published in the Annals of Physics. His work is summarised in the two books Thermodynamics (1897) and Theory of Thermal Radiation (1906). In 1926, he was elected to Foreign Membership of the Royal Society and in 1928, he was honoured with the Society’s Copley Medal. During the Nazi regime in Germany, Planck experienced a difficult and tragic period in his life in which he felt it was his duty to remain in his country, but openly opposed some of the government’s measures, particularly the persecution of Jews. He experienced a personal tragedy when one of his sons was executed for his involvement in a failed assassination attempt on Hitler in 1944. He died in Göttingen on fourth of October 1947.

He was revered by his colleagues not only for the importance of his discoveries, but also for his great personal qualities. He was a gifted pianist and considered music as a profession.

Max Karl Ernst Ludwig Planck was born in Kiel, Germany, on April 23, 1858, the son of Julius Wilhelm and Emma (née Patzig) Planck. His father was Professor of Constitutional Law in the University of Kiel, and later in Göttingen. Planck studied at the Universities of Munich and Berlin, where his teachers included Kirchhoff and Helmholtz, and received his doctorate of philosophy at Munich in 1879. He was Privatdozent in Munich from 1880 to 1885, then Associate Professor of Theoretical Physics at Kiel until 1889, in which year he succeeded Kirchhoff as Professor at Berlin University, where he remained until his retirement in 1926. Afterwards he became President of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Promotion of Science, a post he held until 1937.

The Prussian Academy of Sciences appointed him a member in 1894 and Permanent Secretary in 1912. Planck’s earliest work was on the subject of thermodynamics, an interest he acquired from his studies under Kirchhoff, whom he greatly admired, and very considerably from reading R. Clausius’ publications. He published papers on entropy, on thermoelectric ity and on the theory of dilute solutions. At the same time also the problems of radiation processes engaged his attention and he showed that these were to be considered as electromagnetic in nature. From these studies he was led to the problem of the distribution of energy in the spectrum of full radiation. Experimental observations on the wavelength distribution of the energy emitted by a black body as a function of temperature were at variance with the predictions of classical physics.

Planck was able to deduce the relationship between the ener gy and the frequency of radiation. In a paper published in 1900, he announced his derivation of the relationship: this was based on the revolutionary idea that the energy emitted by a resonator could only take on discrete values or quanta. The energy for a resonator of frequency v is hv where h is a universal constant, now called Planck’s constant. This was not only Planck’s most important work but also marked a turning point in the history of physics. The importance of the discovery, with its far-reaching effect on classical physics, was not appreciated at first. However the evidence for its validi ty gradually became overwhelming as its application accounted for many discrepancies between observed phenomena and classical theory.

Among these applications and developments may be mentioned Einstein’s explanation of the photoelectric effect. Planck’s work on the quantum theory, as it came to be known, was published in the Annalen der Physik. His work is summarized in two books Thermodynamik (Thermodynamics) (1897) and Theorie der Wärmestrahlung (Theory of heat radiat ion) (1906). He was elected to Foreign Membership of the Royal Society in 1926, being awarded the Society’s Copley Medal in 1928. Planck faced a troubled and tragic period in his life during the period of the Nazi government in Germany, when he felt it his duty to remain in his country but was openly opposed to some of the Government’s policies, particularly as regards the persecuti on of the Jews.

In the last weeks of the war he suffered great hardship after his home was destroyed by bombing. He was revered by his colleagues not only for the importance of his discoveries but for his great personal qualities. He was also a gifted pianist and is said to have at one time considered music as a career. Planck was twice married. Upon his appointment, in 1885, to Associate Professor in his native town Kiel he married a friend of his childhood, Marie Merck, who died in 1909. He remarried her cousin Marga von Hösslin.

Three of his children died young, leaving him with two sons. He suffered a personal tragedy when one of them was executed for his part in an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Hitler in 1944.

He died at Göttingen on October 4, 1947.

Paul Sacher

1906 Basel – 1999 Basel

The Basel conductor Paul Sacher (1906-1999) devoted himself to the contemporary music of his century as a performer, as a commissioner of new compositions and as a patron and member of numerous committees and institutions. As early as 1926, he put together his first orchestra, the Basel Chamber Orchestra (BKO), which existed until 1987. This was followed in 1941 by the founding of the Collegium Musicum Zürich (CMZ), which remained active until 1992. While the programmes of the BKO in particular were strongly influenced by the juxtaposition of old and new music that was popular in the early 20th century, the repertoire also opened up to avant-garde trends of the second half of the century in later decades.

From the very beginning, one of Paul Sacher’s most important concerns was to commission new works for his orchestras. In addition to composers from his personal circle such as Conrad Beck, Willy Burkhard and Frank Martin, he soon contacted international greats such as Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky and Paul Hindemith. He was later joined by names such as Luciano Berio, Elliott Carter, Cristóbal Halffter, Hans Werner Henze, Heinz Holliger and Wolfgang Rihm – to name but a few. The commissions were followed by occasional gifts of manuscripts, which formed the foundation of the later Paul Sacher Collection. In many cases, the professional contacts turned into friendships, which later created the necessary basis of trust for the composers or their heirs to place entire collections of autograph documents in the hands of the Paul Sacher Foundation. Sacher provided the initial impetus for this by acquiring the estate of Igor Stravinsky in 1983 and, shortly afterwards, the collections of Anton Webern and Bruno Maderna for the Foundation – the path to an international research archive was mapped out.